What were the academic accomplishments of the first women on the faculty?

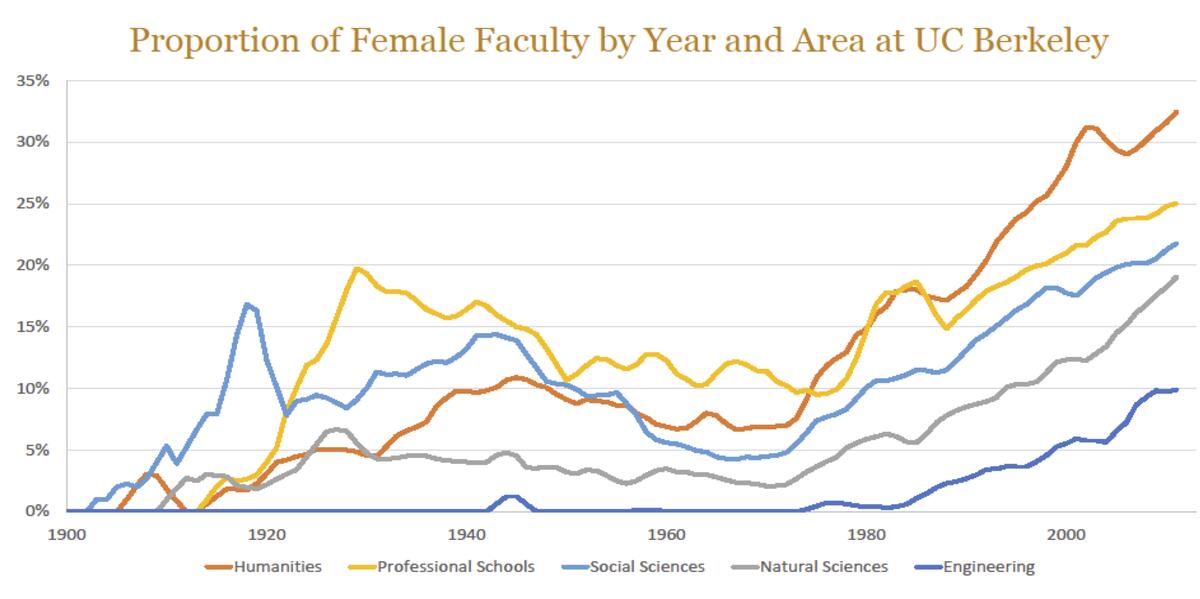

Between 1915 and 1919, the female percentage of the social science faculty rose from 7% to 16%, the highest proportion in any division. The rise probably reflects the founding of Home Economics and its original placement in the College of Letters (now Letters and Science). The growth “Social Economics” inside the Economics Department also contributed several social sciences faculty in these years, including Jessica Peixotto. Then, as professional programs and schools were formed in the 1920s, some women faculty seem to have migrated to those units. Home Economics Science became an independent unit. The percentage of women in social sciences dropped sharply between 1920 and 1929 (from 19% to 9%); concomitantly, the percentage of women in the professional school faculty rose from 4% in 1920 to 20% in 1930, reflecting larger changes in the number of such programs and the fields of professional training. In short, the chart records not a rise and decline of different faculty in two areas, but the arrival of many women faculty in the years leading up to 1920 and then their reclassification in the subsequent decade. It’s a picture of the disciplinary and institutional flux surrounding the first cohort of faculty women.

An example of the disciplinary elasticity of these pioneers can be seen in the career path of Dr. Olga Bridgman, a pioneer in child psychology and development. Since the field had not yet come into existence, Bridgman combined several different kinds of training. She came to California in 1913, two years after getting her M.D. from the University of Michigan. At Berkeley she earned a master’s and a doctorate, and in 1920, we find her listed as an Assistant Professor of Philosophy teaching “Abnormal Psychology”. Concurrently, she taught Pediatrics at UCSF. Only in 1922 did she find a more appropriate home in the newly created Psychology Department. She continued researching and teaching at both UCSF and Berkeley for forty years.

An example of the disciplinary elasticity of these pioneers can be seen in the career path of Dr. Olga Bridgman, a pioneer in child psychology and development. Since the field had not yet come into existence, Bridgman combined several different kinds of training. She came to California in 1913, two years after getting her M.D. from the University of Michigan. At Berkeley she earned a master’s and a doctorate, and in 1920, we find her listed as an Assistant Professor of Philosophy teaching “Abnormal Psychology”. Concurrently, she taught Pediatrics at UCSF. Only in 1922 did she find a more appropriate home in the newly created Psychology Department. She continued researching and teaching at both UCSF and Berkeley for forty years.

For all of their variety, though, the new disciplines opening to female faculty did have something in common. They were already feminized fields, for educated middle-class women had worked in them on a voluntary basis for decades. They emerged in the context of the socialization, professionalization, and increasing governmental oversight of activities that had traditionally belonged to women: community healthcare and hygiene; charity and community relief; childcare and education; nutrition and household production and management. Through churches, women’s clubs, and private charities, they tried to solve such pressing social and medical problems as educating slum children, feeding, and clothing families, caring for orphans, establishing clinics and infirmities, and combating urban delinquency and rural poverty. Then in the early decades of the twentieth century, it became obvious that the scale of the problems was too large for private charities and volunteer organizations. Government resources were needed, which came with state oversight and certification, leading universities throughout the country to offer professional training in new academic programs (Solomon, 83-90; 137-140).

The professionalization of these sectors in California created the need for academic preparation and eventually the formation of either new departments or special schools and programs at the university. We can see this private-to-public dynamic at work, for example, in the career of alumna, and later Lecturer, Katharine Felton, who graduated from Berkeley in 1895, received graduate training in Political Economy at the University of Chicago, and was made the Director of the Associated Charities of San Francisco in 1901. That position brought her to prominence as a chief organizer and administrator of the coordinated federal, state, and city emergency relief efforts following the 1906 earthquake and fire. Her influence on San Francisco’s social services continued for decades; she reorganized the care of orphans in the city, pioneering the move to foster homes from impersonal orphanages (Leiby, 174-180; Sprague, 198-99).

In the twenties, the work Felton had initiated and coordinated through private charities was taken over by public agencies, and she smoothly transitioned to a public administrative role, which made her especially interested in the training and qualifications of the many young women who joined the new profession of social worker. Planning for their education kept her connected to her alma mater, where she not only helped develop a Curriculum in Social Service but also taught as a Lecturer in the Department of Social Welfare from 1926 to 1940 (Academic Senate, 1940(link is external)).

Perhaps the best known—and most controversial—example of women’s work becoming an academic discipline, though, was the creation of Home Economics departments throughout the country in the first decades of the century. Members of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae at first disapproved, fearing Home Economics would downgrade women’s college education by reducing it to household training, which would merely channel women back into homemaking. But others saw Home Economics as an opening for women in the sciences, they thought it would make “household management, scientific cookery, and sanitary science legitimate areas of scientific inquiry” (Nerad, 34). Many hoped that university programs in the subject would raise the status of women’s work generally while opening more faculty positions to women (Solomon, 85-88). The debate may have been short-circuited by the requirement of home economics in public high schools, which forced colleges to train teachers in the subject. Nevertheless, ambivalence about its effect on the status of women faculty continued.

Berkeley’s experience with a Home Economics Department illustrated that both sides of the debate were right: the department both quickly raised the number of women on the faculty and also marginalized them. As historian Maresi Nerad explains, Home Economics had the full support of President Benjamin Ide Wheeler, who initiated its departmentalization in 1916 and thought the unit would provide vocational training for homemakers. The women faculty, however, viewed themselves not just as teachers but also as researchers seeking new evidence about daily life that might ultimately yield fundamental theoretical insights. Because the university in general had such a limited view of the field, though, the women it recruited had to struggle constantly for space, meager resources, academic legitimacy, and recognition of their accomplishments (Nerad, 17-71).

A few new faculty women brought into the university through Home Economics, like the nutritionist and department chair Agnes Fay Morgan, managed to carry on crucial research and make important discoveries within its confines. A person of unusual focus and determination, Morgan put off motherhood until after her promotion to full professor in 1923, even then keeping the fact under wraps. As one colleague recalled, “her research was in chemistry, and so she usually wore a long smock, and when her son arrived on the scene, everybody was startled because nobody knew that he was on his way” (Nerad, 77). She studied the biochemistry of vitamins and the nutritional value of foods, while shaping the entire department and building one of the most important programs in human nutrition in the country. Nevertheless, her research was repeatedly thwarted by lack of money and inadequate facilities. Underfunded by the university, she sought money from California’s food industries for analyzing such topics as the effects of canning on the vitamins in tomatoes. For that unapproved initiative, the university cut her research budget even further. After many such struggles, she eventually gained recognition as a scientist: the American Chemical Society awarded her its Garvan Medal in 1949, and the Berkeley Academic Senate chose her to be the first woman Faculty Research Lecturer in 1951. In 1962, after her division of Home Economics had been rechristened the Department of Nutritional Sciences, the building housing it was renamed Morgan Hall.

A few new faculty women brought into the university through Home Economics, like the nutritionist and department chair Agnes Fay Morgan, managed to carry on crucial research and make important discoveries within its confines. A person of unusual focus and determination, Morgan put off motherhood until after her promotion to full professor in 1923, even then keeping the fact under wraps. As one colleague recalled, “her research was in chemistry, and so she usually wore a long smock, and when her son arrived on the scene, everybody was startled because nobody knew that he was on his way” (Nerad, 77). She studied the biochemistry of vitamins and the nutritional value of foods, while shaping the entire department and building one of the most important programs in human nutrition in the country. Nevertheless, her research was repeatedly thwarted by lack of money and inadequate facilities. Underfunded by the university, she sought money from California’s food industries for analyzing such topics as the effects of canning on the vitamins in tomatoes. For that unapproved initiative, the university cut her research budget even further. After many such struggles, she eventually gained recognition as a scientist: the American Chemical Society awarded her its Garvan Medal in 1949, and the Berkeley Academic Senate chose her to be the first woman Faculty Research Lecturer in 1951. In 1962, after her division of Home Economics had been rechristened the Department of Nutritional Sciences, the building housing it was renamed Morgan Hall.

Despite the hard-won eminence ultimately achieved by Morgan and a few of her colleagues, the devaluation of the Home Economics sciences as women’s vocational education kept the junior faculty from finding space and money to undertake their own research. The department thus had trouble retaining the younger women it recruited. Finally, in the early 1960s, when high schools stopped requiring home economics courses, it was disbanded. The program in Nutrition stayed at Berkeley, and other divisions of Home Economics moved to the Davis campus.

The first women faculty often found themselves relegated to feminized areas of research, which were marginalized. Their separation, though, did allow them to create new areas of interdisciplinary inquiry, and their efforts were encouraged and sometimes even mandated by the era’s growing public service sector. These developments made women university teachers and researchers much more common. Nevertheless, their status and tenure too often remained insecure, and their fields tended to stay on the periphery of academic interest.

New Women in Old Fields

There were also, to be sure, academic women teaching in more traditional academic departments in 1919-20. What can be learned from comparing a few of their career paths with those of the women in the new fields?

One department with four faculty, Physiology, included two women, Rosalind Wulzen and Lillian Moore, as Instructors. Both women had received their PhDs from Berkeley within the previous six years. Although Instructor was a common entry-level title for both men and women at the time, Wulzen held it for fourteen years, from 1914 until 1928, when she resigned to take an assistant professorship at the University of Oregon. Her departure from Berkeley is described by Nello Pace as part of an “upgrade” for a stagnating and overly inbred department (Pace, 12). And yet in Oregon, where she found support for her research, she made the important discovery of a compound in molasses and unpasteurized cream—which was named the Wulzen factor after her—that could protect the joints of mammals against calcification. She taught at both the University of Oregon’s Eugene campus and at Oregon State in Corvallis, finally settling into the Zoology Department there and retiring as a full professor in 1954 (https://oregondigital.org/sets/osu-historical-images/oregondigital:df72j633v(link is external)). The year after Wulzen moved to Oregon, Lillian Moore (who had been promoted to Assistant Professor) died suddenly of a rare blood cell disorder. Except for a one-year stint by Dr. Evelyn Anderson Haymaker (later a professor at UCSF), the Department of Physiology appears not to have employed anymore faculty women until the 1950s, when the unit was merged with Anatomy (Pace, 12-16).

Wulzen’s career pattern of very slow or even non-existent progress into and through the professorial ranks, was common for faculty women in this period. Annie Biddle, for example, was the first woman to be awarded a PhD by the Berkeley Mathematics Department in 1911. After marrying in 1914, she began teaching, holding titles usually given to graduate students: teaching fellow, assistant, associate. The titles may indicate that she preferred part-time teaching because she’d started a family. Finally, she was made Instructor in 1924, a decade after earning her PhD. But when the economic depression hit and the department was forced to reduce its size, she was laid off on the grounds that she was a married woman whose husband could support her (Greene and LaDuke, “Andrews, Annie Dale Biddle”). This pattern became prevalent in the following decades, when married women were repeatedly told that men needed their jobs. Wulzen’s and Biddle’s experience might also indicate that women who entered departments where they’d earned their doctorates had a difficult time overcoming their previous status as graduate students; it might have looked as though they were hired partly because they were readily available.

Even women coming from other prestigious graduate programs often made slow progress through the ranks and retired without tenure. Alice Post Tabor came to the German Department with a PhD from Chicago in 1916. For sixteen years, she taught as an Instructor at every level—including graduate seminars in German Literature—until she was finally given an Assistant Professorship in 1932. Looking at the Department course lists in 1920, we see three PhDs with Instructorships, two men and Tabor. In 1930, only one, Tabor, had not been moved to the professorial ladder. In 1948 when Tabor retired as an Assistant Professor, both the men had long held tenured professorships. It appears that women did not necessarily benefit by coming from outside the institution. Nor did they have an easier time in longer established or more stable and traditional departments. Where they were competing with more men, they faced different kinds of challenges from those encountered in the feminized fields.

* * *

Thus, Professor Peixotto was the only woman hired by the university deliberately to serve on the faculty during the first four decades of its existence. Peixotto’s influence at the university went far beyond her individual teaching and research. She led the wing of “Social Economics” in the Economics Department, which was a forerunner of the School of Social Welfare. Moreover, President Wheeler charged her with the responsibility of chairing a faculty committee to determine the function and organization of a Home Economics program at Berkeley (Nerad, 51-63). The task was difficult, time-consuming, and controversial, but it eventually led to the founding of a new department with a predominantly female faculty.

Thus, Professor Peixotto was the only woman hired by the university deliberately to serve on the faculty during the first four decades of its existence. Peixotto’s influence at the university went far beyond her individual teaching and research. She led the wing of “Social Economics” in the Economics Department, which was a forerunner of the School of Social Welfare. Moreover, President Wheeler charged her with the responsibility of chairing a faculty committee to determine the function and organization of a Home Economics program at Berkeley (Nerad, 51-63). The task was difficult, time-consuming, and controversial, but it eventually led to the founding of a new department with a predominantly female faculty.