The most important new circumstance affecting women students in the 1890s was the swift and disproportionate growth in their numbers. Women’s enrollment increased almost ten-fold during the decade: in 1889, there were just 87 women on campus, by 1898, the number had jumped to 819 and stood at 41% of the student body. At the end of the decade, the “President’s Biennial Report” described the rising proportion of women for the last four years of the decade—“1896-7, 39.94; 1897-98, 42.2; 1898-99, 44.33; 1899-1900, 46”—and predicted that women would be 48% in the coming year. Men’s enrollment during the decade increased only 3.3 times. The overall increase in the student body was due to the state’s growing population, and the steeper rise in women might be partly attributed to the fact that in 1893 California had started to require the baccalaureate degree for high school teachers. According to the President’s report, they congregated in the “General” as opposed to “Technical” colleges, making up “nearly two-thirds of the students in the Colleges of Letters, Social Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Commerce”. Their academic concentration also seemed to indicate the women’s intention to become teachers (“Biennial Report”, 1898-1900, 13).

No doubt their increase in numbers exacerbated some of women’s problems, especially the dearth of places to live and enjoy recreation, but it also made them more visible while exposing their exclusion from student organizations as increasingly unjust and unreasonable. Concentrating in larger groups and becoming majorities in some fields also made it more likely that they would begin to create their own organizations for extracurricular activities.

Moreover, the upturn in women’s enrollments at Berkeley in the 1890s was part of a larger regional trend toward producing college-educated women. Mills College in Oakland had been chartered to award the baccalaureate in 1885, and Stanford had opened as a full-scale co-educational university across the bay in Palo Alto in 1891. As the first institution that could truly compete with Berkeley for the region’s intellectually ambitious women, Stanford had some real advantages that UC women immediately noticed. Both universities were tuition-free, and both had faculties mainly recruited from the Ivy League. But Stanford started out with many amenities that Berkeley had only acquired piecemeal through private donations (the library, the men’s gym) or had no intention of building (a chapel, an art museum, and dining halls). Most importantly, it had dormitories for both men and women.

Berkeley alumna (1880) and future Ph.D. recipient (1898) Millicent Shinn published an article about the new Stanford campus just before it opened, in which she admired the facilities but also somewhat defensively contrasted them with the lack of housing at her alma mater: “I have more than once heard [UC] President Gilman . . . hold up for imitation the university that saved the most from housing itself to spend on great teachers, perfect laboratories, endowment of research” (Shinn, 1891, 342). Further developing the contrast, she remarked that Stanford’s impressive structures “could only have been done by a rich man building his own university; no board of regents spending trust funds for the State” could have built so lavishly. But even as she defended the UC Regents’ no-housing policy, she could not restrain her enthusiasm for the Stanford dormitories, which were to have elevators, steam heat, bathrooms on every floor, and even electric lights! Stanford’s treatment of its students threatened to cast Berkeley in an unflattering light.

By the end of the century, though, a potential disadvantage for women of private university control had also become evident. Throughout the 1890s, the growth in the proportion of women in Stanford’s student body kept pace with the rise of women at Berkeley, leaping from 25% in 1892 to 40% in 1899 (Rudolph, 323-4). But at that point, Jane Stanford (then widowed and heir to her husband’s estate) had the power to impose a cap on any further growth. She froze female enrollment at 500, and the limitation stayed in place until the 1930s as the numbers of male students increased greatly. At public Berkeley, no such restrictions would have been legal.

The example of Stanford was also important for the woman who would be the first appointed to UC’s Board of Regents: Phoebe Apperson Hearst. Her arrival as benefactor was another of the important new circumstance of the 1890s. When women students began articulating their needs, organizing their own activities, and finding patrons to support them, she was the most munificent of their champions. A former schoolteacher and the widow of millionaire George Hearst, she had long had an interest in supporting education.

By the time Hearst was appointed a Regent in 1897, she had already been supporting women students since 1891, the year in which Stanford opened. She could easily see that some women students were living in poverty at Berkeley, and so she endowed scholarships exclusively for them to cover their room and board. Also aware that women had no place to gather and organize on campus, she held frequent receptions for them in her Berkeley home, helping to consolidate them into a community (Kantor, 5-7). Once appointed a Regent, she gave the women students a voice in the halls of power for the first time.

Hearst’s encouragement, along with that of Dr. Mary Ritter (their medical examiner), furthered the students’ campus organizing, and they also made alliances with other women’s organizations that were forming around the university. The Association of Collegiate Alumnae, for example, established a branch in San Francisco in the mid-1890s, and many Berkeley alumnae, who felt unwelcome in the university’s Alumni Association, became active members (Park, 25; Clifford, 1998, 91). The organization of faculty wives was another source of support, as were community church women who helped in the creation, starting in 1889, of the YWCA, which adjoined campus and became, like Hearst Hall, a center of women’s activity (Clemens, 11-19).

A dynamic synergy was thereby established, which would carry forward into the early decades of the twentieth century: women students cultivated allies among well-established women in the community (alumnae, wives of faculty, and other community leaders) who would help them expand the roles for women at Berkeley.

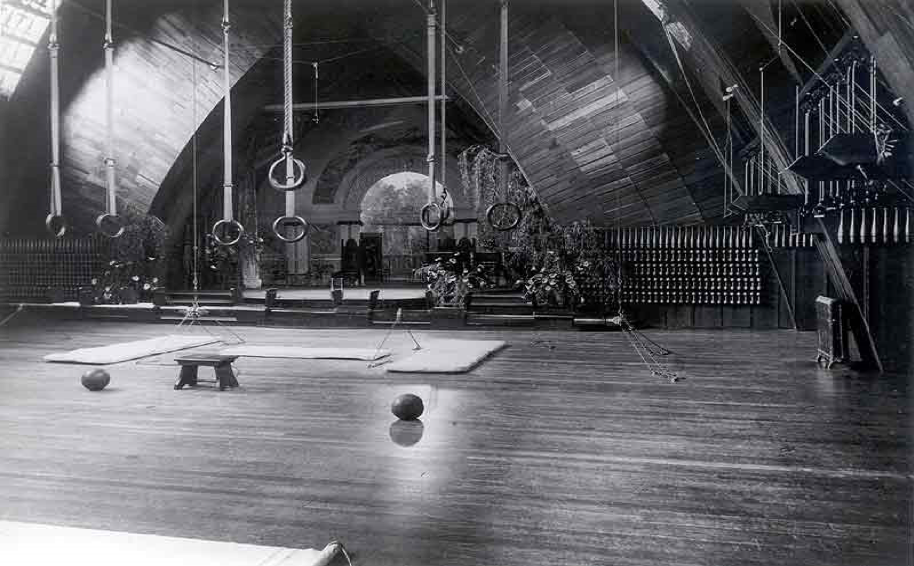

Hearst Gym